Original Study

July 2019, 26:3

First online: 31 July 2019

Original Study

Bigger or Smaller? Common Coronary Stent Diameters Used Amongst Malaysian Patients

Kien Chien Lim,1 Rohith Stanislaus,2 Kumara Gurupparan3

Contact: Kien Chien Lim, dr.limkc@ijn.com.my

Address: National Heart Institute, 145, Jalan Tun Razak, 50400 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

We aim to examine the common coronary stent diameter used in respective coronary tree segments and their differences between the gender, the primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) status as well as diabetes mellitus group.

METHODS

A total of 11401 patients with 12906 de-novo lesions treated with non-overlapping stents from January 2011 till December 2015 were analyzed. The patients were divided between the gender, the primary PCI status, and the status of diabetes mellitus.

RESULTS

A total of 11401 patients were included in which 10800 (83.7%) were male, 6739 (52.0%) had diabetes mellitus and 1746 (13.5%) had primary PCI. The median (IQR) stent diameter for LM was 3.50mm (3.50-4.00), proximal LAD was 3.00mm (2.75-3.00), mid LAD was 2.75mm (2.50-3.00), distal LAD was 2.50mm (2.25-2.75), proximal LCx was 2.75mm (2.50-3.00), distal LCx was 2.50mm (2.50-2.75), proximal RCA was 3.00mm (3.00-3.50), mid RCA was 3.00mm (2.75-3.50), and distal RCA was 2.75mm (2.50-3.00) There was significant gender difference in the stent diameter in all coronary artery segments except the LMS (p= 0.99), distal LAD (p= 0.73), and distal LCX (p= 0.085). The diabetes mellitus group had significant smaller coronary stent diameter in all coronary segments except the LM (p=0.33) and proximal LCX (p=0.21). However, there was no significant difference in stent diameter between the primary PCI and non-primary PCI group.

CONCLUSIONS

Coronary stent diameters are generally smaller in the female gender and in patients with diabetes mellitus. However, left main stent diameters are similar regardless gender and diabetes status.

KEYWORDS

1) Coronary stent diameter 2) Stent Sizing

INTRODUCTION

Choosing the appropriate coronary stent diameter during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a real challenge to many operators especially the beginners. This fundamental step not only predict the angioplasty success, but also the long term outcome. PCI with an undersized coronary stent diameter remains the independent predictor of in stent restenosis, in stent thrombosis, repeat revascularization and adverse cardiac events.1, 2 In contrary, larger stent diameter induces trauma to the vessel and therefore more edge dissection and more coronary perforation.

Most operators determine the coronary stent diameter by using visual estimate of the coronary angiogram (reference vessel diameter) or quantitative coronary angiography (QCA). Despite the proven superiority of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) guided PCI over angiographic guided PCI in reducing restenosis, repeat revascularization and major adverse cardiovascular event, IVUS is still under-utilized in many centers.3-8 Reason for the underutilization in our region are cost and availability. The use of intracoronary imaging in our center was about 5%.

In angiographic guided PCI, the coronary stent diameter is determined by the distal luminal reference diameter. Therefore, underestimation of stent diameter usually occur with a small reference coronary segment. Causes of small reference coronary artery are Asian populations,9 female gender10 diabetes mellitus11 and vasoconstriction of infarct related artery during acute myocardial infarction.12

Female gender and patients with diabetes mellitus are known to have smaller coronary arteries but the common coronary stent diameters used are not reported. Hence, the aims of this study are to examine the common coronary stent diameter used in each segment of the coronary tree, as well as the diameter differences between the gender group, the primary PCI status and the diabetes mellitus status.

METHODS

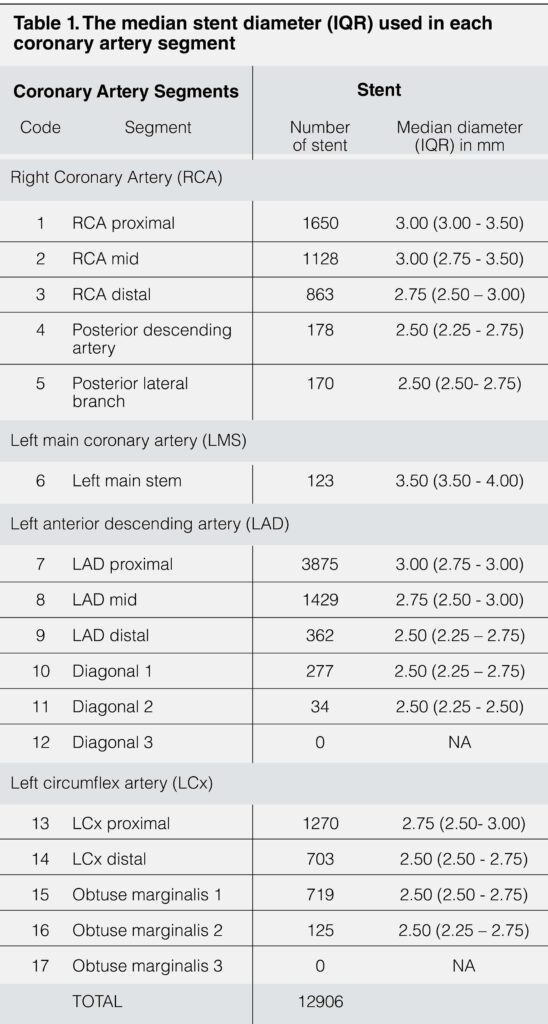

We analyze patients’ data from the National Heart Institute PCI registry from January 2011 to December 2015. It was a cross sectional study involving the patients with de-novo lesions receiving non overlapping stents on the left main artery (LM), left anterior descending artery (LAD), left circumflex artery (LCx) and right coronary artery (RCA). Each coronary artery segments was labeled with code as per figure 1. We excluded the overlapping stents and the bypass graft vessels stenting. The stent diameter in regards to the each coronary artery segments were compared between the gender, the diabetes mellitus group, and the primary PCI group. The result was analyzed with MedCalc version 17.8.6 statistical tool. The median coronary stent diameters were compared among groups using Mann-Whitney rank sum test.

Figure 1

Coronary artery tree segments and codes

RESULTS

CORONARY ARTERY SEGMENTS

There were 11401 patients included in our study. A total of 12906 de-novo lesions treated with non-overlapping stents were analyzed. 11800 (83.7%) were male patients, 6739 (52.0%) had diabetes mellitus and 1746 (13.5%) had primary PCI for ST elevation myocardial infarction. The largest stent diameter used was 4.0mm and the smallest stent diameter used was 2.25mm. Majority of the stents were implanted at the proximal segment (n=6918, 53.6%), followed by mid segment (n=2557, 19.8%), distal segment (n=1928, 14.9%), and major artery branches (n=1503, 11.6%). There was no stent implanted in the diagonal 3 branch and obtuse marginalis 3 branch. Proximal LAD had most stents implanted (n=3875, 30.0%), followed by proximal RCA (n=1650, 12.8%) and mid LAD (n=1429, 11.1%). The median stent diameter for each segments of the coronary arteries are shown in table 1. The proximal segments received bigger stent compared to the segment distally and their major branches with the exception of proximal RCA (3.00mm, IQR 3.00-3.50) and mid RCA (3.00mm, IQR 2.75-3.50).

PRIMARY PCI STATUS

Only 1746 patients (13.5%) had primary PCI for ST elevation myocardial infarction. The median diameters used in primary PCI group were not significantly differ from the non-primary PCI group (table 2).

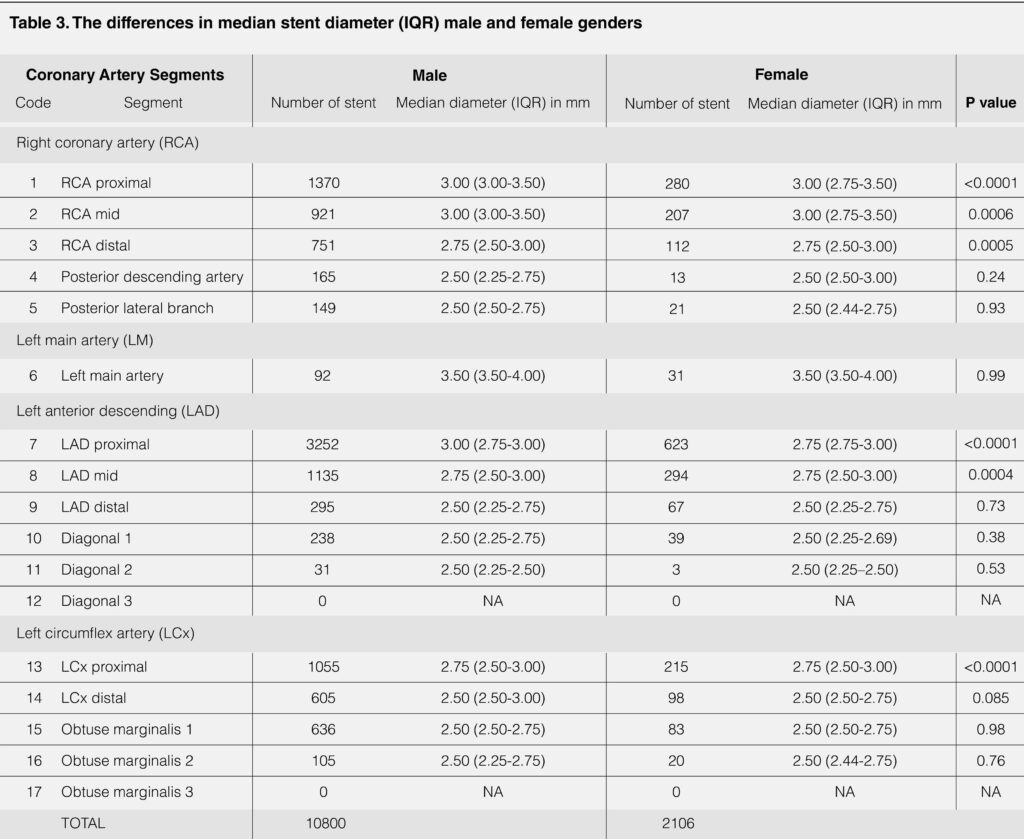

GENDER DIFFERENCES

Majority of the de-novo lesions were from the male gender group (n=10800, 83.7%). The stent diameters used in the male group were significantly bigger than the female group in all proximal and mid coronary artery segments with the exception of left main artery (3.50mm, IQR 3.50-4.00, p=0.99) (table 3).

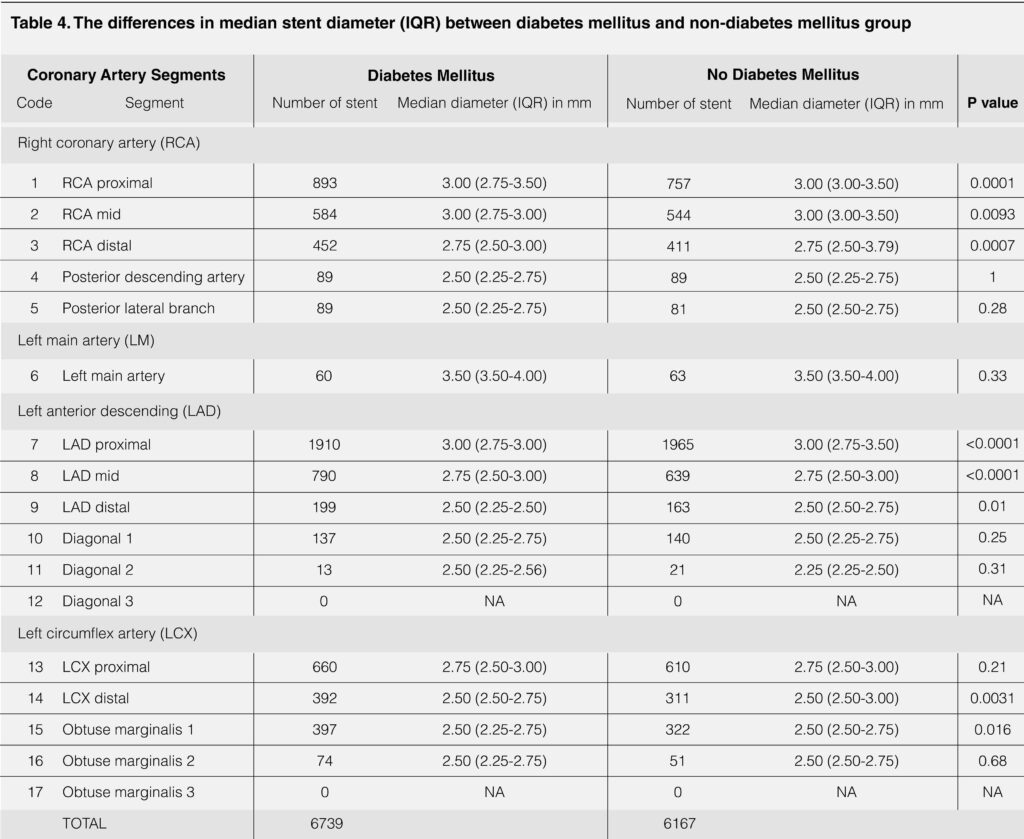

DIABETES MELLITUS STATUS

6739 patients (52.0%) had diabetes mellitus. The coronary stent diameters were significantly smaller in the diabetes mellitus group for all major coronary artery segments with the exception of left main artery (3.50mm, IQR 3.50-4.00, p=0.33), proximal LCx (2.75mm, IQR 2.50-3.00, p=0.21) and their major branches (table 4).

DISCUSSIONS

The coronary artery stent diameters in our study were expressed in median with interquartile range for each coronary artery segments. The proximal and mid vessels were our interest of observation as the lesions appeared to be uniformly located in these segments with increased shear stress. However, the RCA and LCx coronary segments stent diameters should be interpreted carefully as the system dominance was not being analyzed in this study.

One important finding in our study is that- the median coronary stent diameter used in the left main artery was 3.50mm (IQR 3.50-4.00) regardless the primary PCI status, gender and 3 diabetes mellitus status. Thus, it is important to compliment your decision making with intra-coronary imaging if a smaller stent would be used. Intracoronary imaging guided PCI is always the recommendation for the left main artery stenting.

The common myth of smaller stent diameters used in the infarct related artery was not demonstrated in this observational study. The release of vasoconstrictor mediators during acute myocardial infarction causing did not translate into the clinical use of a smaller stent diameter during the primary angioplasty. Thence, recommended strategies to avoid undersizing the coronary arteries are 1) optimal use of intra coronary vasodilators, 2) intra-vascular ultrasound guidance PCI, and 3) considering to stage the procedure.

Our finding of women having smaller coronary arteries with the exception of left main artery is consistent with the PROSPECT study (Providing Regional Observations to Study Predictors ofEvents in the Coronary Tree).13

The coronary stent diameters used in our population were generally smaller in the diabetes mellitus group. This finding was consolidated by the study done by Kip KE14 and Selva JA15 which demonstrated that patients with diabetes mellitus have small coronary reference diameter as a consequences of higher plaque burden and more diffuse disease.

Lastly, it is important to mention that the median stent diameters were compared using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test, which is a rank sum test and not a median test. Therefore, the test can still be significance despite having the same median diameters.

LIMITATIONS

Other factors that might affect the coronary artery size such as body surface area, races are not included in our study.

CONCLUSION

Coronary stent diameters are generally smaller in the female patients and in patients with diabetes mellitus. However, left main stent diameters are similar regardless gender and diabetes status. The stent diameter used in the primary PCI setting were not significantly differ in the non- primary PCI group. Stent diameter tables in our observational study adds value to the basic of coronary angioplasty, however, do not replace the routine steps of stent size selection.

REFERENCES

1.Heribert Schunkert, Lari Harrell, Igor F. Palacios. Implications of Small Reference Vessel Diameter in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Revascularization. Journal of the American College of Cardiology Vol. 34, No. 1,1999;41-48. CrossRef Pubmed

2. I-Chang Hsieh, Ming-Jer Hsieh, Shang-Hung Chang et. Al. Vessel Size and Long-Term Outcomes After Limus-Based Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation Focusing on Medium and Small-Diameter Vessels. Angiology 2017, Vol. 68(6) 535-541. CrossRef Pubmed

3. Zhang Y, Farooq V, Garcia-Garcia HM, et al. Comparison of intravascular ultrasound versus angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation: a meta-analysis of one randomised trial and ten observational studies involving 19,619 patients. EuroIntervention 2012;8:855-65. CrossRef Pubmed

4. Klersy C, Ferlini M, Raisaro A, et al. Use of IVUS guided coronary stenting with drug eluting stent: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials and high quality observational studies. Int J Cardiol 2013;170:54-63. CrossRef Pubmed

5. Jang JS, Song YJ, Kang W, et al. Intravascular ultrasound-guided implantation of drug-eluting stents to improve outcome: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7:233-43. CrossRef Pubmed

6. Ahn JM, Kang SJ, Yoon SH, et al. Meta-analysis of outcomes after intravascular ultrasound-guided versus angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation in 26,503 patients enrolled in three randomized trials and 14 observational studies. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:1338-47. CrossRef Pubmed

7. Zhang YJ, Pang S, Chen XY, et al. Comparison of intravascular ultrasound guided versus angiography guided drug eluting stent implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2015;15:153. CrossRef Pubmed

8. Elgendy IY, Mahmoud A, Elgendy AY, Bavry A. Outcomes With Intravascular Ultrasound-Guided Stent Implantation: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials in the Era of Drug-Eluting Stents. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9:e003700. CrossRef Pubmed

9. Amgad N. Makaryus, Bhupesh Dhama, Jagdeep Raince et.al. Coronary Artery Diameter as a Risk Factor for Acute Coronary Syndromes in Asian-Indians. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:778–780. CrossRef Pubmed

10. Jaya Chandrasekhar, Roxana Mehran. Sex-Based Differences in Acute Coronary Syndromes: Insights From Invasive and Noninvasive Coronary Technologies. JACC Cardiovascular Imaging Vol.9, No 4, 2016. CrossRef Pubmed

11. Mosseri M , Nahir M, Rozenman Y, et al. Diffuse narrowing of coronary arteries in diabetic patients: the earliest phase of coronary artery disease. Cardiology 1998;89:103–10. CrossRef Pubmed

12. Maseri A, Davies G, Hackett D, et al. Coronary artery spasm and vasoconstriction. The case for a distinction. Circulation 1990;81:1983-91. CrossRef Pubmed

13. Wykrzykowska JJ, Mintz GS, Garcia-Garcia HM, et al. Longitudinal distribution of plaque burden and necrotic core-rich plaques in nonculprit lesions of patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol Img 2012;5:S10–8. CrossRef Pubmed

14. Kip KE, Faxon DP, Detre KM, et al. Coronary angioplasty in diabetic patients. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty Registry. Circulation 1996;94:1818–25. CrossRef Pubmed

15. Silva JA, Escobar A, Collins TJ, et al. Unstable angina. A comparison of angioscopic findings between diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Circulation 1995;92:1731– 6. CrossRef Pubmed

Copyright Information